What the Trees Say

From the New York Review of Books

The Long, Long Life of Trees

The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate—Discoveries from a Secret World

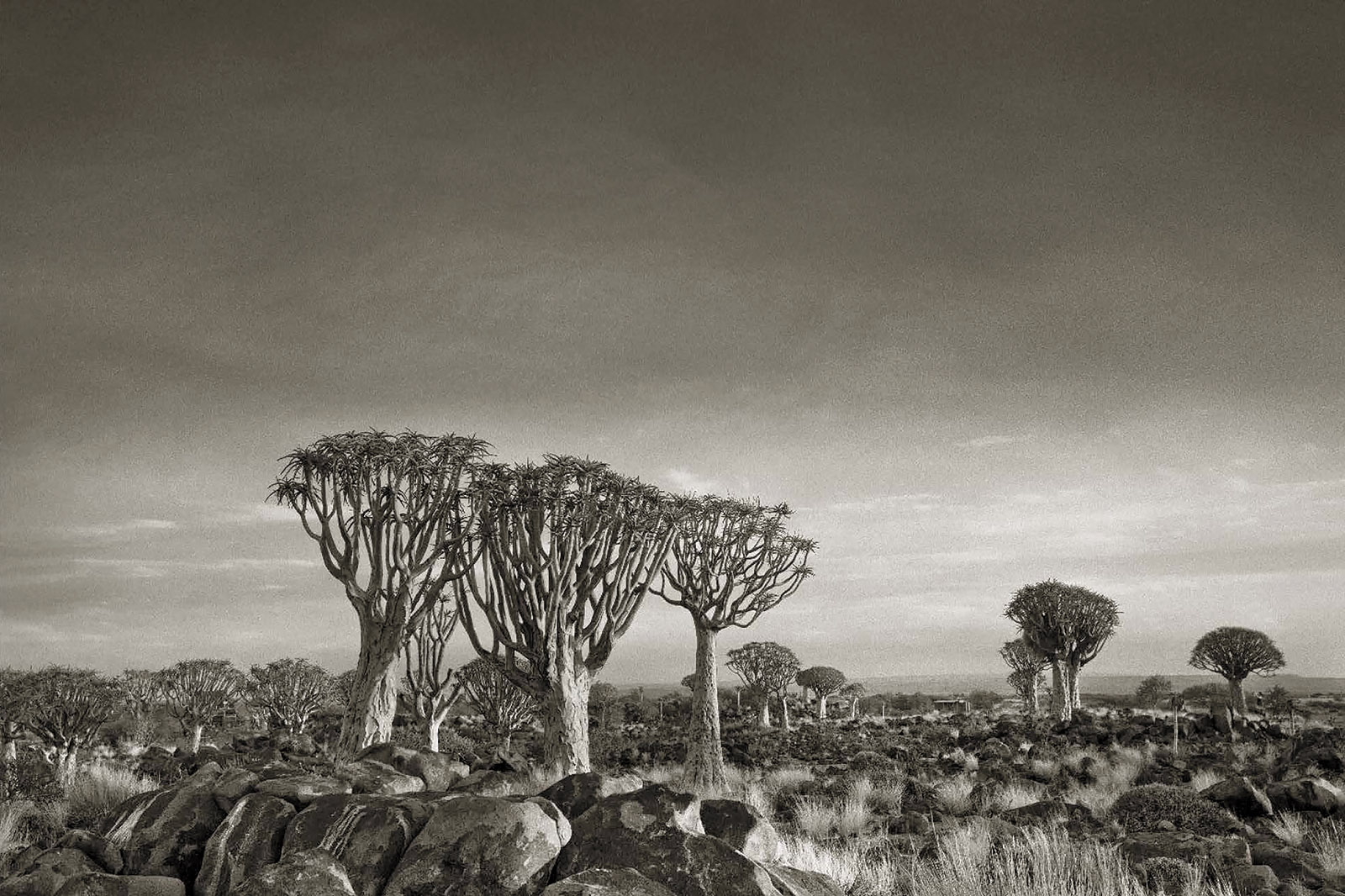

Quiver Tree Forest, Namibia; photograph by Beth Moon from her book Ancient Trees: Portraits of Time (2014). A collection of her color photographs, Ancient Skies, Ancient Trees, has just been published by Abbeville.

In 1664 John Evelyn, diarist, country gentleman, and commissioner at the court of Charles II, produced his monumental book on trees: Sylva, or a Discourse of Forest Trees. It was a seventeenth-century best seller. Evelyn was a true son of the Renaissance. His book is learned and witty and practical and passionate all by turns. No later book on trees has ever had such an impact on the British public. His message? A very modern one. We are in desperate need of trees for all kinds of reasons. Get out there with your spade and plant one today.

Despite the catastrophes that crippled London in the next two years—the great plague and the great fire—Evelyn lived to see the book reprinted four times. A century later it was reissued with elegant copperplate illustrations and an exhaustive commentary to bring it up to date. Later editions of the book (renamed Silva) have followed, and many authors have tried to write in the spirit of Evelyn. But somehow Sylva has always remained head and shoulders above its successors. That is, until the present. The two new books on trees under review are both outstanding. In different ways their authors share many of Evelyn’s best qualities.

Fiona Stafford’s The Long, Long Life of Trees treads closest in the footsteps of Sylva. Evelyn, it is true, was more adventurous in his choice of trees to be described in detail. He covers an astonishing range: a tally of thirty-one genera, which include newly introduced trees from the American East Coast, like red oaks and Weymouth pines, as well as trees that were seen as exotic in England, such as the cedar of Lebanon and the Irish strawberry-tree. Stafford plays safe by choosing a mere seventeen genera, which represent the common trees of gardens and woods and hedgerows throughout Western Europe as well as North America: oaks, sycamores, chestnuts, hawthorns, and so on. But there is nothing humdrum about her descriptions.

Stafford is professor of English at Oxford University and writes about novels, poetry, art, and the environment. In her own way she is as learned as Evelyn, and she is a gifted writer. What do trees mean for her? She owes this book, she says, to her “sense of wonder” at trees. She admires their physical beauty. She is astonished by their gift for survival. And most of all, perhaps, she is struck by their extensive cultural associations. She reminds us that it’s easy to take trees for granted. But we must do more than merely admire them. We must go out there, she says, echoing Evelyn’s words, taking our spades to plant new saplings for the future.

If she plants a tree, her first choice, I feel sure, will be an oak. Most sensible people find the common oak of Europe, Quercus robur, quite irresistible. Ever been inside a Royal Oak? Stafford means the British pub, not the famous oak at Boscobel in which the future Charles II hid from the fury of the Roundheads after his defeat at the Battle of Worcester in 1651. Of course one led to the other, and today there are more Royal Oaks in Britain than any other pubs except Crowns and Red Lions.

In her chapter on oaks, Stafford explores the tangled history of Britain’s infatuation with the species. It long predates the king’s miraculous escape at Boscobel. The oak was a symbol of power and strength from classical times. It was the tree of Zeus, king of the gods. It was the oracular tree at Dodona in Greece, meaning that it could predict the future. Augustus Caesar, ever conscious of his image, faced the Roman public wearing a civic crown of oak leaves. The tree’s “manly” virtues made it a choice as a symbol for any country, like Britain, seeking to impress its neighbors. Effortlessly it became the national tree of Britain, although the claim was not uncontested. (Many patriotic British people would be surprised to learn that twelve other European countries and the US all claim it as their national tree.)

“Sturdy, stalwart and stubborn,” Stafford writes,

the oak has always been admired for its staying power…. No other tree is so self-possessed, so evidently at one with the world. Unlike the beech, horse chestnut or sycamore, whose branches reach up towards the sky, the solid, craggy trunk of a mature oak spreads out, as if with open arms, to create a vast hemisphere of thick, clotted leaves.

It is this copious canopy that provides a home for an astonishing number of small insects, birds, animals, lichens, ferns, and fungi. If you look up at those mossy, fern-encrusted branches, you may well find redstarts and robins and wood warblers searching for insects, while woodpeckers and little owls build their nests in hollows in the trunk. A great oak is a world in itself. “This is the King of the Trees,” Stafford writes exultantly, “the head, heart and habitat of an entire civilisation.”

How long can a great oak survive? Sober estimates are impossible, since the oldest oaks are invariably hollow, and most of the annual rings are therefore missing. Wild estimates (including my own) vary between six hundred and one thousand years. Fortunately, many of the great oaks of Britain were engraved and described by Jacob Strutt for his pioneering set of tree portraits, Sylva Britannica, first published in 1826. (He borrowed half his title from John Evelyn.) As one would expect, the majority of Strutt’s ancient trees—the Yardley oak, the Bull oak, the Cowthorpe oak—have now been blown down or simply crumbled to dust. Others have been reduced, like the Major oak in Sherwood Forest, to the fate of a cripple supported by steel crutches. But a few of the most famous have survived.

“Majesty” at Fredville in Kent still stands tall, after perhaps five or six hundred years. The Panshanger Oak in Hertfordshire, much admired by Winston Churchill a century ago, still looks good for several more centuries. Even more remarkable is the Bowthorpe Oak in Lincolnshire. Stafford describes a visit she paid to this aged creature. My guess is that it’s at least seven hundred years old. At any rate its trunk was hollow enough in the eighteenth century for smart dinner parties for seventeen people to be given inside its vast interior. Now it’s only the home of a pony and some chickens. But its generous owner allows visitors. Stafford describes the experience: “like stepping from ordinary domesticity into the presence of some immortal being—ancient, wrinkled, yet oddly welcoming.”

Read the rest of the review here.